NewsPerspectives

Back to the Future

Shortly after the Canterbury earthquakes I wrote about what we could expect of the new buildings, and how their design would respond to influences of lightness, speed and cost. Elapsed time has shown my insights and predictions for the built future to have been largely accurate.

On reflection, eight years on from September 2010, I offer these new thoughts:

- Heritage buildings are cultural artefacts floating (untethered?) in a sea of new construction.

- It makes sense in a context of our future identity to rescue these artefacts, to ensure we retain connection with ourselves, and with our cultural backstory.

- This connection is essential to inform and guide the present, and the future.

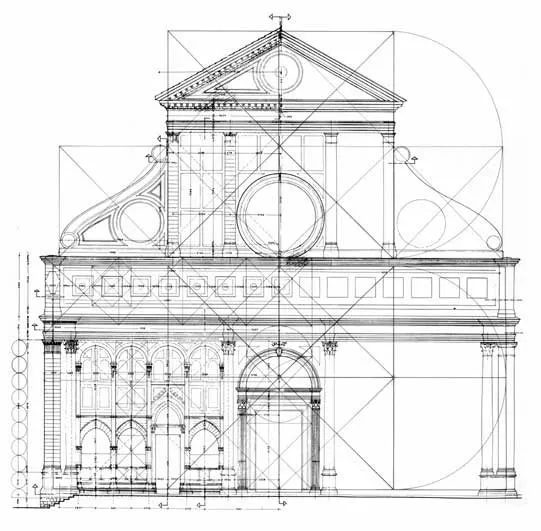

Our success with recent reinstatement and restoration projects across New Zealand is linked to renewal, to an understanding that buildings must continue to be useful. Some changes are necessary, even desirable, to allow buildings to better fit with the present and the future - but their essence and originality as cultural artefacts is retained. Combining these outcomes is the key to success and ongoing value. On the one hand, considerations of performance (resilience and comfort) are important; but these should be balanced against more nebulous concerns of meaning, how buildings make us feel, and our cultural trajectory.

Cultural identity is important in 2018, and for me, connections to colonial buildings, and through these, insights to earlier generations, resonate strongly. In our new city, why would we choose to sever these connections for future Cantabrians? And further, if we do not value our past, how might we ascribe value to the future?

Of late, there has been debate in response to heritage restoration planning, and proposed ratepayer/taxpayer expenditure on heritage buildings in the future. And it is not unreasonable that such spending should be discussed. The question is one of value: what value is being retained, what value generated? These buildings represent the resolve and expenditure of previous generations, and their perception of continued viability in the future. Capital and effort optimistically committed in times of prosperity, or carefully expended in times of austerity. We are now - once again - experiencing times of uncertainty and doubt, in which old orders are in question, and new patterns emerging. Such a context of volatility and disruption offers insight and is the correct moment to take steps ensure that the artefacts of our past can be protected to survive and thrive in the future.

All things we make carry stories forward in time, and rarity contributes to the value of an artefact and its story. Our heritage buildings are now truly rare, and we can readily draw parallels to art and other human endeavour. Art is easily understood as a finite output of its creator. Obsolete and decommissioned technologies – for example classic racing cars (and classic racing yachts) - put aside by owners in pursuit of the new and improved, now also carry high value and unique identity. If we can understand the painstaking restoration of these reconsidered artefacts from our past, an equivalent building restoration can be also understood in terms of preservation of rarity, identity and value.

The Christchurch Town Hall is an example to discuss. The building, completed in 1972 but with a gestation of some 20 years, was a summation of Christchurch’s aspiration for civic expression, finally realised after decades in planning, fundraising, and determined effort by the city leaders of the day. Its contemporary, the Sydney Opera House, was designed and built in those same years, and the contrast between them is illuminating. Where the Sydney building reacts to its harbour setting, Christchurch’s Town Hall is rugged, rocky, mountainous and gutsy – in line with its Lord of the Rings southern setting and its commissioning by a rural services town with big plans for the future. Two decades of prosperity in Canterbury resulted in a building of ultra-high specification and world-recognised design quality. In real terms, the Town Hall of 1972 was arguably beyond what we as a city could afford to commission today. So why might we contemplate its demolition, particularly when a contemporary replacement would be more expensive, potentially of lesser quality, and its construction certainly delayed beyond 2020?

When the reconstruction/restoration project is complete next year, we will achieve a significant architectural outcome: one which preserves our identity, is fit for purpose, and - less obviously - reconciles the time value of money. The Town Hall will be fully updated to contemporary technical standards reflecting requirements of today’s performances and audiences. On opening it will be a building we will have paid for in yesterday’s dollars, not tomorrow’s, and the cost – and associated value - to ratepayers will reflect this foresight.

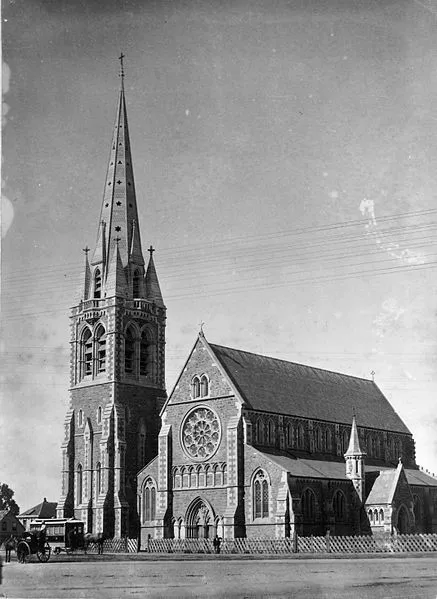

Like the Isaac Theatre Royal and the Arts Centre, the Town Hall will be as-new, aligned with today’s aspirations, and ready to embrace the future. It can do so without severing links to the past. The opportunities presented by the Christ Church Cathedral, the McDougall Art Gallery, The Provincial Council buildings, and others, to similarly capture our identity for the future are ones we should embrace, and with enthusiasm. Such buildings are our taonga, and they carry us forward through time.

Richard McGowan is an architect and Principal at Warren and Mahoney. He has recently been involved in the restoration/rebuild of the Isaac Theatre Royal, the Christchurch Club, the Arts Centre, and the new CSO building at the Christchurch Town Hall.